Everybody knows that in our imperfect world, we face many man-made threats — including pollution, global warming, habitat loss, and species extinction, to name a few. However, these threats often seem distant, with no immediate impact on our daily lives, so they’re largely ignored. Yes, we acknowledge that science has proven these threats real and increasingly dangerous, but their predicted grim effects lie somewhere in the future — and mankind is not known for its patience.

However, this attitude has changed quite abruptly over the last few years with one specific man-made threat: the accumulation of plastics in the human body.

It has been known since the 2010s that man-made nanoplastic and microplastic particles (MNPs) take residence in human tissues, but their effects were initially unknown. A 2019 study found MNPs in all human stool samples analyzed (source). In 2022, researchers detected microplastics in human blood as well (source). Detected particles were typically under 700 nanometers (nanoplastics), but some were larger (micro-scale, up to 20 micrometers). The most common types were:

- PET (polyethylene terephthalate – water bottles)

- PE (polyethylene – packaging)

- PS (polystyrene – Styrofoam cups/containers)

- PVC (polyvinyl chloride – water pipes)

It was suggested these particles can float freely, bind to proteins, or be absorbed by immune cells. However, no direct health effects were confirmed at that stage.

That changed with a groundbreaking study published in 2024 by Marfela et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (source). A team from three Italian universities studied patients undergoing stent implant surgeries for life-threatening coronary artery disease (CAD). Instead of discarding the atheromas (arterial plaques), researchers analyzed their chemical composition using fluorescent microscopy and HPLC profiling. Astonishingly, 60% of patients had PE, PVC, or both inside their atheromas.

But the biggest shock came from follow-up data: patients whose plaques contained plastics had a 4.5x higher death rate within 36 months after surgery, compared to those with plastic-free plaques. This finding hit the medical community like a bomb. CAD is the #1 cause of death in the U.S. and many developed countries — and if these results are confirmed, it suggests plastics may be killing more people annually than COVID-19 did at its peak before vaccines were available.

This 2024 study sparked an explosion of research on microplastics’ health effects across virtually every medical field. One of the most striking findings was a link between brain microplastic levels and dementia (source). Polyethylene can cross the blood-brain barrier and accumulate in the brain’s fat-rich environment. In fact, brain tissue has higher concentrations of MNPs than the liver, kidneys, or blood. Importantly, patients with diagnosed dementia (e.g., Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS) were found to have up to 30 times higher levels of MNPs compared to healthy brains — especially in cell membranes and brain-resident immune cells.

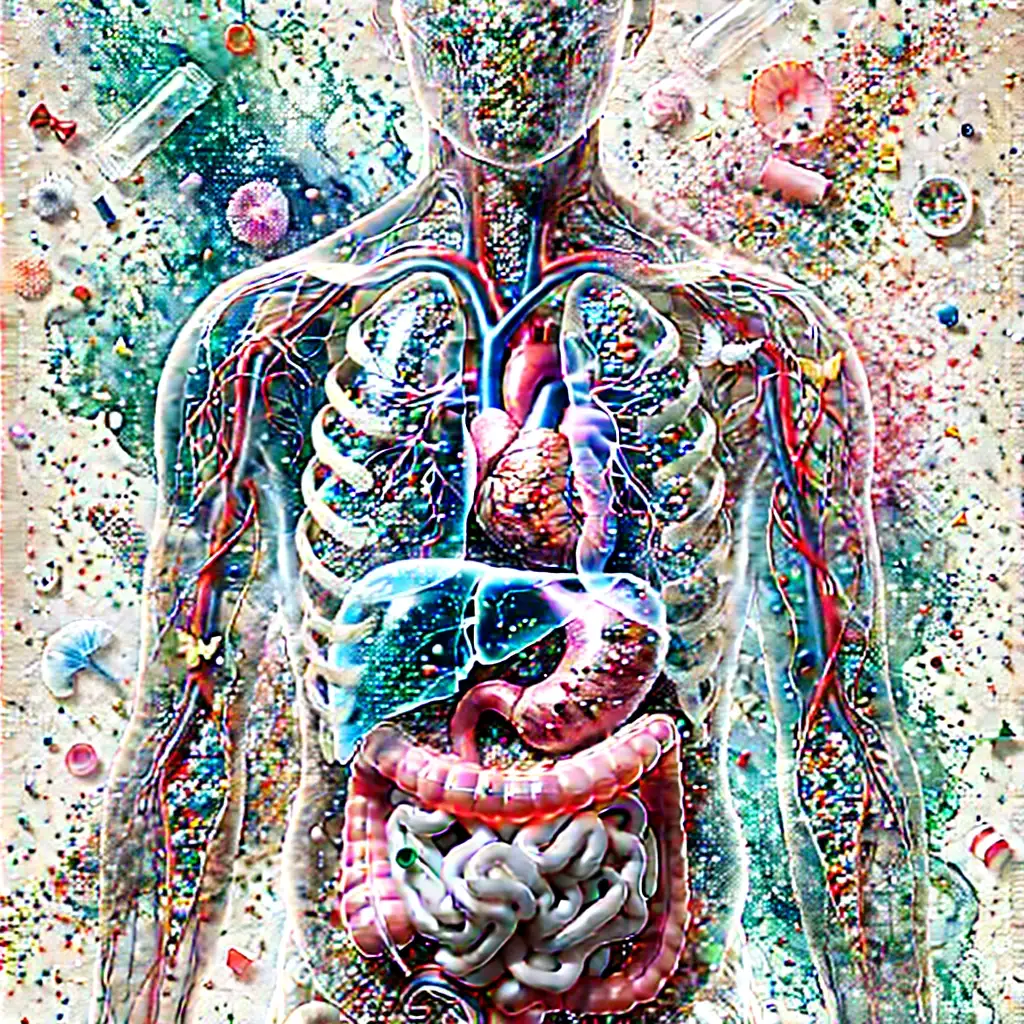

Plastics are now found everywhere in the human body: liver, blood, kidneys, fat, placenta, and even newborn babies (review). According to emerging research, this may be a more dangerous threat than COVID-19 — and far harder to solve. Plastics are chemically inert and polar, meaning our liver’s detox system cannot break them down. Nor can our gut microbes process them.

As a result, research worldwide is now focusing on:

- How MNPs enter the body

- How they spread and where they accumulate

- How they might be safely eliminated

One promising project is underway here at the University of Sharjah (UAE). We’re currently testing the hypothesis that blood microplastic levels can be significantly reduced through ozone oxidation combined with synergistic therapies.